An Interview with Jenn Givhan

On environmental catastrophe, family secrets, and the unrelenting bond between mothers and daughters.

I am positively GIDDY to bring you this interview today, because I absolutely loved Jennifer Givhan’s new novel Salt Bones, which the LA Times called "A triumph . . . One of the most masterful marriages of horror, mystery, thriller, and literary writing."

Jenn is an award-winning Mexican-American and Indigenous poet and novelist from the Southwestern desert. She is the author of four novels—Jubilee, Trinity Sight, River Woman, River Demon, and Salt Bones—as well as five full-length poetry collections. The recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and PEN/Rosenthal Emerging Voices, Givhan weaves stories rooted in motherhood, myth, cultural memory, and the borderlands where she grew up. Her work braids Mexican and Indigenous storytelling traditions with contemporary social issues, exploring environmental justice, ancestral grief, and the fierce love between mothers and daughters. Raised in the Imperial Valley of Southern California, she now lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with her family, where she tends her writing, teaches, and keeps altars to her ancestors and the stories that haunt her.

You will not be disappointed by her answers!

Q: Tell me what inspired Salt Bones, your novel, and whether the story surprised you in any ways as you wrote it.

In the 90s, I grew up near the ancient saline basin once called Lake Cahuilla, which has filled and emptied over millennia in the Southern California desert. In the early 1900s, it was unintentionally remade into the Salton Sea after two floods and a broken dam channeled irrigation water from the Colorado River. By the time I was a kid, ninety years later, my mama warned us it was poison. We could smell for ourselves the fish die-offs, the weeks-long stink of toxic algal blooms.

After I left for college, got married and had kids, I returned to my hometown to visit my comadre, who told me that the Salton Sea was drying up and releasing toxic chemicals like arsenic from decades of pesticide runoff, which had sunk into the lakebed, aerosolized, and wafted into the lungs of everyone still breathing throughout the community. The whole Valley could become a ghost town, she said, if nothing was done.

I started researching and over the next decade, I became increasingly concerned about the fate of the place that raised me, which had been featured in shows like Abandoned America, although the mostly Mexican community is still thriving, even as the farm-owning elite bring in billions in agricultural revenue each year, all while the so-called accidental lake poisons the air. When activists went up to Sacramento to ask for help, legislators had been overheard justifying their apathy with remarks like, “No one lives down there anyway.”

I knew I had to tell this story. My soapbox may have been slippery, but people tend to love murder mysteries. So I wrapped my heart in one.

Around that time, I had a moment every parent dreads: my daughter didn’t come out when the school bell rang, and for several minutes, I thought she was gone. That feral, set-the-world-on-fire panic braided itself into the novel, which morphed from a historical novel set in the 1970s, focused on Mal’s childhood on the Salton Sea, into the contemporary ecological and socio-political outcry it is now for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, told through the voices of Mal and her two daughters. This story is also all my poems, braided together through genre and mythmaking, entangling the characters and the land.

I thought I knew the ending when I started, but I kept the central “monster” hidden even from myself. When it revealed itself in the final act, I was as gutted as Mal. It hurt to write, but I couldn’t turn away.

Q: Did you feel especially “close” to any particular character? I felt like they all were so true to themselves and leapt off the page, and I loved them in different ways. Mal for her sturdy, fierce determination. Amaranta for her passionate youth. Griselda for the way she is torn between the world she comes from and the life she wants beyond El Valle, to name a few. Was it difficult to nail the individual voices of your characters?

Mal is my heart: a flawed, fierce mama doing her best in an impossible world. But her youngest scientist daughter Amaranta’s passionate youth and her eldest college-aged daughter Griselda’s tension between home and the horizon each pulled me in. All three are eco-social-justice warriors in their own ways and remind me of my daughter, myself, and my mom.

I hear my characters’ voices before I see their faces. I think it comes from growing up with tías, comadres, and storytellers who could spin a whole world from a single dicho. My mother is such a worldbuilder and story-weaver. Sometimes I don’t know where her voice ends and mine begins, and my daughter now tells me the same about us. For better or worse, as for Mal and her girls in Salt Bones, who call themselves Las Veracruz Chicas, akin to the Gilmore Girls.

Q: What do you most hope readers of your book will take away from it? What do you fear they might?

I hope readers leave haunted and awakened, with a deeper love for the strong women in their lives and a renewed reverence for marginalized communities. I say at the end of the prologue that no one has seen or heard these girls and women; that no one has said a damn word to anyone. I fear that after reading, they still won’t. I hope they will.

Q: One of your reviewers refers to your novel as a retelling of the Persephone/Demeter story—yet your novel draws upon Mexican cultural mythos (I was particularly taken by La Siguanaba, the horse head woman). Talk to me about the power of myth and the dangers of white washing these important cultural stories.

Myths are living things. In Salt Bones, I braided Demeter and Persephone with La Siguanaba (a monstrous mother and horse-headed woman from Central American and Mexican lore) to show our stories belong beside the Western canon, not beneath it. Whitewashing erases not just the tale, but the land, the language, the people it came from. Reclaiming our myths says our stories have always mattered.

Q: Salt Bones is deeply invested in the fates of missing Latina and indigenous women, many of whose cases end up unsolved. What drove you to write about these stories?

These disappearances are too often ignored, misclassified, or forgotten. As I’ve said before, lawmakers have even dismissed them by saying, “No one lives down there anyway.”

We live there. We matter.

Every name missing from the news is our daughter, sister, mother, auntie. Fiction can’t solve the cases, but it can make their absence impossible to ignore. It can refuse to look away.

When I began writing Mal’s life in the 1970s—loosely paralleling my mother’s but deeply fictionalized—I started uncovering the trauma she faced. I realized I was a first daughter born of a first daughter of a first daughter, as far back as I could think. What happened to me had happened to her, to my grandmother, to my great-grandmother. I felt called to heal that ancestral wound, though I couldn’t yet confront the specific violence we endured.

So the Spirits gave me another path: to confront the larger injustices—the machismo, patriarchy, and misogyny that harm women and girls, and the white supremacy that makes it even harder for brown girls to survive. Salt Bones is my way of making sure we women are seen, heard, and never forgotten.

Q: How do you go about plotting your stories? Detailed outline? Organic notes? Wing it? How long does it take you to revise a novel?

I plot obsessively, filling several notebooks for each novel, but as my dear friend and fellow writer Sarina Dahlan (Reset, Blackstone) says, “I’ll make an outline, but it’s a lie.” Ha!

Though I start at the end to retro-architect the story, I also let the world and characters I’ve created derail me completely by following their messy, real-life responses and sometimes terrible decisions, the kind that show our human hearts and passions and misunderstandings and teach us something about ourselves and the world around us. Since I started writing as a poet, I often think of the advice I’ve accrued over the years—such as the poem is wiser than we are. Or, as Robert Frost said, a poem is like ice on a hot stove that rides its own melting. The same is true for my novels, which are all epic poems of sorts.

Q: Tell me about your creative process. Are there any tools, practices, rituals, influences that go into creating for you?

Writing is absolutely a ritual and has helped me deepen my connection to my Ancestors. As I’ve practiced brujería and curanderismo over the years, I began building portable altars—spaces to honor the sacred wherever I am. Sometimes that means lighting candles beside the bathtub while I soak to ease chronic pain. Sometimes that means placing my grandmother’s photo next to my laptop. All of these rituals, large and small, help open portals to the underbelly, which I often liken to the Upside Down in Stranger Things, where I’m able to transmute story.

My spiritual practices have taught me to be gentler with myself. If I can’t write on a particular day, it isn’t failure, but rest, which can be sacred, fertile, and resistance. These altars remind me that the sacred is already within. The Muse is already here; my job is to quiet myself and listen.

At the same time, part of the ritual is letting go.

Most mornings, after coffee and hot chocolate with my daughter, I declare: Today I’m gonna write something UGLY! We growl and stomp and chant it together—UGLY! MESSY! FERAL! WEIRD! That ritual permits me to show up as I am—brain fog, chronic illness, self-doubt demons and all. I follow my unruly characters through the fog and trust the story will find me.

Q: Did anything in your own book make you cry as you wrote it? Can you tell us about that without too many spoilers?

To write with as much love, care, hope, and tenderness as I did, I had to pretend not to know the dark truth, in a sense, to learn and discover it with my characters. Even though I plot like mad, many twists and revelations occur spontaneously while drafting and revising. I love the magic of writing.

Realizing the sick roots at the heart of the story hurt like hell, but it was a painful truth I couldn’t turn away from. I had to stay strong, like Mal, for her girls. “Don’t look away,” I’d remind myself while writing.

So Mal’s journey enlightened and healed me in many ways, as she’s a strong and flawed badass mama who protects her daughters and herself even after she’s messed up. Healing is not linear, but cyclical. We mamas can delve back into the underbelly, defying physics with our motherlove, and heal both past and present, making choices rooted in the refusal to look away.

Q: If you are at or near midlife—how is this time of life affecting you? Are there any glimmers of truth, understanding or wisdom you’ve gained, even if hard won? If you are past it, what advice do you have for others in midlife from your own experience?

After early life trauma, every stage has felt like the end and the beginning at once. I’ve carried an old soul inside me since I was a little girl. So now, at 41, every moment feels like a bonus stage—the Fool’s Journey in tarot, stepping out each day into the unknown with open hands.

Midlife has taught me that the second half of life isn’t about chasing what you missed in the first. It’s about savoring what’s here now.

Living the now is still hardest for me, but I’m learning.

Q: The title of this Substack is “Writing in the Pause”—and while it’s a nod to the physical stage of perimenopause, it’s also a reminder that we could all benefit from more pauses. Tell us about them, how they work, and what they mean to you.

The work of decolonization can sometimes become so soul-heavy, it feels unbearable. That’s when I know it’s time to rest and return to my family, go inward to my altar, or come back to writing, depending on where I am in the cycle. I remind myself that our stories have always been circular. We return to where we began, but with new perspective: gifts of insight, love, hope, or tools we’ve gathered from previous journeys.

The Western messaging I’ve internalized, even unintentionally, can sometimes make me feel worthless or hopeless—a rat on a wheel, perpetually spinning. But then I remember that I’m a strong, powerful chingona on a spirit-led, heart-filled mission—dancing, chanting, holding, nourishing, nurturing, speaking out for those along the path. Even as I wind down, I rise again, spiraling through the seasons.

My gift is motherwriting, mothering and writing inextricably linked. So when I find myself soul-searching, wondering why I want more, I realize that’s not the true desire, not the seed planted in my by Spirit. That’s the capitalist mindset, ego-fed and empty. What I truly want isn’t more; it’s deeper: connection, love, understanding. Speaking out. Listening.

I pause often, for naps, for playing, for staring out windows at the trees. These are all integral to the writing and the living. Lately I’ve been longing to hold onto the joy, and I sense pausing even more is the ticket.

Even as I amass more credits and awards, etc., I’ve realized the deep need to pause from self-criticism and impossible standards. I’ve been Hermione my whole life. I’ve thrived on other peoples’ surprise and praise of all I could accomplish.

I’m ready not to give any more flying effs what anyone else thinks, good or bad.

Ready to press not just pause but full-on STOP on every opinion that isn’t my own heart.

Q: What impact do you hope to make on your readers? On your community or the world?

We are not alone, dear ones. Badasses. Warriors. Mamas and aunties and grandmothers and comadres and healers and storytellers and dreamers and believers and scientists and teachers and historians and beloveds. We walk through the hellscape together, carrying each other—

Carrying each other back home.

Q: Is there anything else you’d like to share with my readers?

Mal’s tres leches cake is real, and the recipe is in my free book club kit on my website. Bake it, eat it, maybe cry a little into the milky dough. That’s part of the healing.

The other thing is please light your velas (candles) with me as LatinWE and a team of screenwriters take this to the adaptation phase.

Learn more about Jenn:

Insta: https://www.instagram.com/jenngivhan/

About Salt Bones:

Malamar Veracruz has never left the dust-choked town of El Valle. Here, Mal has done her best to build a good life: She’s raised two children, worked hard, and tried to forget the painful, unexplained disappearance of her sister, Elena. When another local girl goes missing, Mal plunges into a fresh yet familiar nightmare. As a desperate Mal hunts for answers, her search becomes increasingly tangled with inscrutable visions of a horse-headed woman, a local legend who Mal feels compelled to follow. Mal’s perspective is joined by the voices of her two daughters, all three of whom must work to uncover the truth about the missing girls in their community before it's too late.

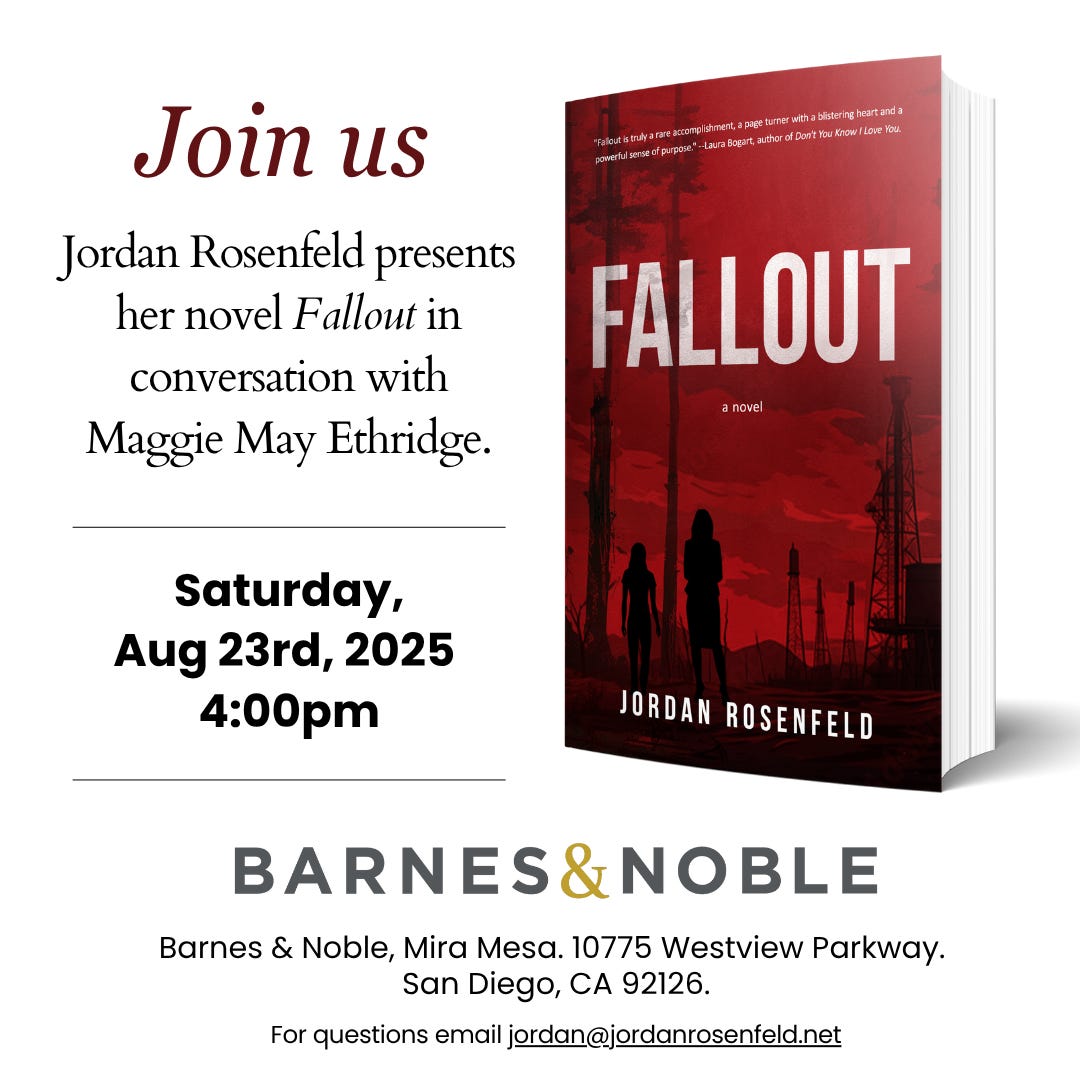

Next Up On the Fallout Book Tour

August 23. I’ll be in San Diego—first at the San Diego Book Festival with Vicki DeArmon of Sibylline Press.

4pm: I’ll be in conversation/reading with Maggie May Ethridge at Barnes & Noble, Mira Mesa on Westview Parkway in SD.

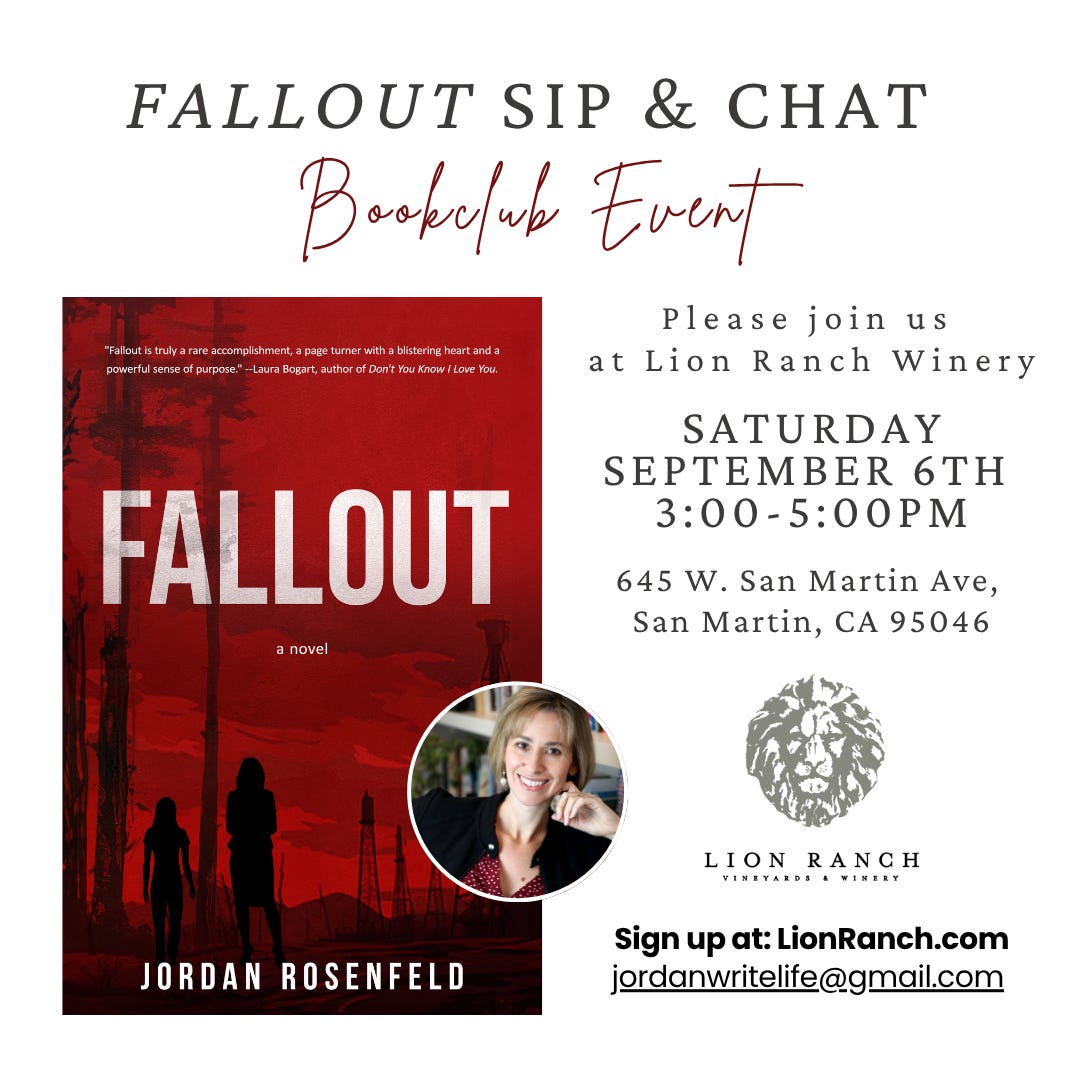

September 6, 3 to 5 pm. Lion Ranch Winery. Sip + Chat. Join me at the gorgeous Lion Ranch Winery in San Martin as we chat, talk books, play literary games and sip wine. A $10 ticket gets you guaranteed admission and a glass of wine!

AND MORE:

Sept. 10, 6pm. “Writing At the Root.” In conversation with Becca Lawton at Readers’ Books, Sonoma, CA.

Sept. 21 Brooklyn Book Festival with Sibylline Press.

Sept. 26-27. Central Coast Writers Conference.

Oct. 25: Elk Grove Writers Conference + LitQuake

Purchase Books!

Purchasing books supports not just me, but the entire small press machinery behind me, including Running Wild Press and Sibylline Press.

I love this interview! Thanks for sharing it.